I like to think, and if I think hard about it it is true,

that my mother and I were close when I was younger (up until I was fifteen or

so). I didn’t go out much, preferred home and my own thoughts. When I rambled, Mom

listened. My mother was what would be termed now a stay-at-home mom, a SAHM.

The term then was housewife, as though one was married to the house and, for a

lot of women, I’m sure that’s how it felt. She cooked for us all, she cleaned, she

made clothes, she grew a garden and canned, she crocheted and embroidered, she kept

the books for Dad, she paid the bills, while we were at school and Dad was in

the woods or driving truck, she was the ranch foreman, she looked after her

mother, she chauffeured and shopped, attended sporting events and baked for bake

sales; she was the chief cook and bottle washer (literally, the year we had twelve

bummer lambs). I have never asked her if she was happy then, or if she is happy

now. I am remiss. (The thirty (plus) year estrangement my father imposed frayed

all tethers; I can still pull a thread tighter; repairs can be made.)

This week my sister tells me that after Mom’s last doctor appointment

they returned to the car to hear that the Capitol was under siege; my mother began

to seethe. And though she has not voted Republican much over the years she has always

been a registered Republican. She’s going to change that. And because she does

not have anything to do with the Internet, I imagine her down at the County

Clerk’s office pen in hand. Probably on a day when she needs to pick

up books at the library as the courthouse is across the street and if one needs

to go out for anything now, combine errands.

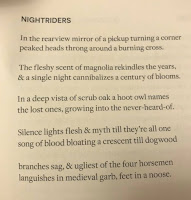

I have this older poem, I’ll post, before I start a letter

to my mother. Think about how to ask for forgiveness. Be safe, be kind.

I never wrote a poem for my mother

Opening the sachet drawer, everything of memory

falls into place: the spool knob handles, the diesel stained

coveralls hung by the door. Laundry, bleached, line dried,

starched and ironed. The whole day process that she

went through. The tub, the ringer, running the hose from

the hot water in the kitchen sink. The line, the board, the

old

Seven-Up bottle for sprinkling. Even the soap

had been a process, a box of lye soap and flakes, top shelf

in the cellar, above the golden and garnet jars

canned each summer. She made the soap, cooking

it on the porch. And on the periphery, between this,

the ungrateful children moved through the house.

Off to bike, off to swim, off to curl on a bed with

a cat and a book. She made clothes and waxed furniture

played the piano, grew cabbage and potatoes, butchered

and plucked and cooked chicken. Was the work a greater

meditation? I don’t remember her ever reading to me,

but her books, a string of thread marking them, perched

on the counter by the bread, she was making

slid from the top of the laundry basket, held down

a pattern she was cutting. Did she welcome the sun

like we did? Ours, a chance to be out, while she stayed

at home, the house humming with only her thoughts

knowing that by noon we’d be in, that she’d have

to think about dinner, that somewhere in the late

afternoon, supper, my father’s return. His clothes

covered in the talc dust of the woods, pine pitch stuck

to his hands as he swung down off the truck.

I don’t recall him ever asking how her day was, what

we did, how was she.

But then neither did we, ask. Satisfied

that this was drudgery and what was there to ask about.